- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Organising

- Podcasts

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Switzerland

- Technology

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

According to the author of a new incident analysis, there's more to the 2012 loss of the cruiseship Costa Concordia than investigations at the time led us to believe. Andrew Linington reports.

Vital lessons about the safety of ships and the wellbeing of seafarers are in danger of being lost because of failures in the way in which the 2012 Costa Concordia disaster was investigated, a meeting in London heard last month.

Nautilus Council member Captain Michael Lloyd told the packed seminar onboard HQS Wellington that the accident had highlighted many of the things that are wrong in the shipping industry - including the lack of proper governance - but its wider significance has been overlooked.

'Had it not been for the vagaries of the wind that blew the ship back to the coast, this could have been one of the worst accidents in peacetime history,' he pointed out.

Just 32 of the 3,229 passengers and 1,023 crew onboard Costa Concordia died when the 114,147gt vessel capsized after hitting a rock off the island of Giglio, and Capt Lloyd has produced a 150-page analysis of the incident, providing an

alternative to the widely-criticised Italian investigation report.

'As I worked my way through the various documents and accounts, I began to realise that there was far more to this casualty than what I had been led to believe by the official and media reports,' he explained.

With the company and five individuals – including the first and third officers, the helmsman and the designated person ashore – having secured plea bargaining agreements with the Italian authorities, responsibility for the accident has been placed on the master, Captain Francesco Schettino.

Capt Lloyd said his report had not been produced as an attempt to exonerate Capt Schettino 'from his many errors of judgement made on that night', but rather to examine the reasons for the accident and the scope for making changes that would prevent similar accidents in future.

He told the meeting, which was organised by the Honourable Company of Master Mariners and the Nautical Institute, that there is evidence that many other cruiseships carried out sail-by 'salutes' in coastal waters – and that another Costa ship, Fortuna, was damaged after hitting rocks off the island of Capri in 2005.

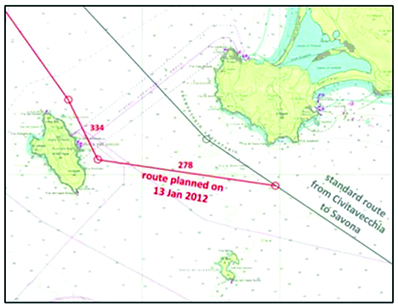

Costa Concordia might have narrowly avoided the rocks off Giglio had it not been for an eight second delay in changing course, which had been identified in analysis of black box and automation system data, Capt Lloyd said.

The delay had been caused by the Indonesian helmsman's difficulty in understanding orders given in Italian, he added. Evidence showed that communications onboard, and most importantly within the operations staff, were chaotic – with the working language of Italian not being understood by the majority of the crew of 46 different nationalities, and many not understanding English.

'It would be, to those not of the marine industry, unbelievable that those on the bridge have difficulty in communicating with each other,' said Capt Lloyd.

'Can you imagine the airline industry behaving in such a fashion?'

Once the ship struck the rocks, breaching five compartments, Capt Schettino appeared to have gone into a state of shock – with the chief officer describing him as being 'out of his routine mental state'.

Capt Lloyd questioned whether it was right, under European human rights law, for the master to be prosecuted when the evidence 'overwhelmingly suggests' that he was affected by trauma, increased by guilt, and was in no way capable of giving orders or properly assessing the situation.

'Post-traumatic stress is recognised by the armed forces, the police, the fire brigades and even industry ashore, so why not at sea?' he noted. 'Why was this not investigated? I cannot imagine a more traumatic event for a captain to

experience, yet the captain's mental state and the staff captain's failure to assume command was never mentioned or discussed at the initial inquiry or the trial, or even the appeal.'

Captain Lloyd said his report had not been produced to exonerate Captain Schettino, but rather to examine the full reasons for the accident and prevent such a thing from happening again

Capt Lloyd said the incident had also demonstrated the inadequacy of life-saving regulations. Problems with davits meant that three of 26 lifeboats could not be launched and only three of the ship's 69 liferafts were launched.

Whilst IMO guidelines recommend a maximum allowable total passengership evacuation time to be in the range of 60 to 80 minutes, it took more than six hours to evacuate Costa Concordia despite its close proximity to land and the

considerable assistance of shore rescue facilities.

The ship's increasing starboard list caused significant difficulties in embarking on survival craft, especially on the port side, Capt Lloyd said. The Italian investigation had failed to adequately assess evidence that even at an angle of 15 degrees, 5 degrees less than the required launching angle, lifeboats could not be launched.

Costa Concordia had theoretical lifeboat capacity for 1,860 passengers on each side, he added. Under the IMO's Life Saving Appliance (LSA) Code, the lifeboats should be boarded within 10 minutes – a rate equivalent to one passenger every four seconds.

However, Capt Lloyd argued, the reality is that such rates are impossible to achieve, and increases in the weight and size of people since the formulae were determined mean that the space and weight allocations defined in the LSA Code are also unrealistic, with studies showing that capacity is over-estimated by around 15%.

The failure to launch so many liferafts might be explained by the fact that a significant proportion of the crew assigned to them lacked the necessary certification or training, Capt Lloyd said.

Following an abandon-ship drill in October 2011, the master had warned the company that the performance of his crew was decreasing and showed critical findings, he added.

Capt Lloyd said the Italian inquiry had missed many facts of seamanship and safety, and ignored key elements of the International Safety Management Code, which clearly states that the captain of a ship cannot be delegated the sole responsibility for the total operation of the ship, as it is the company that has this ultimate responsibility.

Tags